The good news in Africa

.

Robert

Guest

From The World in 2005 print edition

| |

|

|

|

|

|

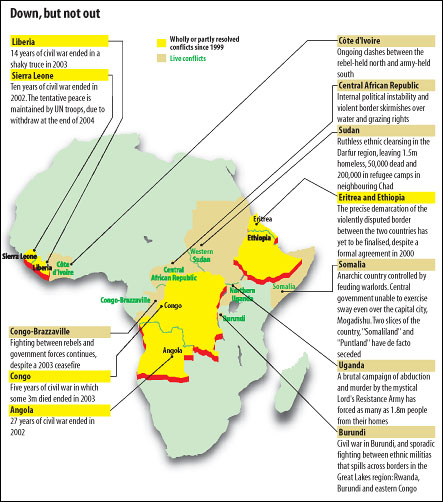

Fewer wars, greater efforts to resolve conflicts

In 2004 the big stories from Africa were the genocide in western Sudan and the tenth anniversary of the genocide in Rwanda. Other news included war in Burundi, communal street fighting in Nigeria and mass displacement in northern Uganda, where 1.8m people have fled their homes to avoid being murdered by an army of child soldiers led by a man who thinks he is the Messiah. All this obscures a surprising trend: as Jean-Marie Guéhenno also notes in The World in 2005, Africa has actually grown more peaceful in recent years.

As recently as 1999 a fifth of Africans lived in nations tortured by war. But civil wars in Sierra Leone, Liberia and Angola appear to be over. A ceasefire ending the pointless border conflict between Ethiopia and Eritrea, in which massed ranks of infantrymen were scythed with machine-gun fire, is still holding. Even the Democratic Republic of Congo is looking better. Though not exactly at peace, it is not gripped by the furious fighting that claimed 3m lives between 1998 and 2003. (As in all African wars, most of these deaths were from war-induced starvation or disease, but hundreds of thousands of people were also killed with bullets or farm tools.)

Africa will be less bloody than news footage suggests, but bloodier than Africans would wish |

What has prompted this sudden outbreak of peace? Some wars ended because the combatants were exhausted. In Angola, for example, after the rebel chief Jonas Savimbi was shot in 2002 his bedraggled followers gave up and formed a political party. Other wars ended because of skilful diplomacy. Liberia was pulled from the inferno when Nigeria persuaded its warmongering president, Charles Taylor, to accept asylum. And outside military intervention has calmed some troublespots. British soldiers helped to rescue Sierra Leone from its hand-chopping rebels, and French and west African peacekeepers have done a reasonable job of keeping the two parties to Côte d’Ivoire’s civil war apart.

For many Africans, peace has brought hope. Refugees are returning home, peasants are planting crops without fear that they will be stolen by passing armies. For the first time in a generation, Angolans can travel around their country without fear of being killed.

But two grave worries remain. One is Sudan, where the atrocious campaign of ethnic cleansing in the western region of Darfur threatens to tear apart Africa’s largest country. The other is that, even in the countries now at peace, the underlying causes of war have often not been addressed. Studies show that civil wars are more likely to occur in countries with bad governments, stagnant economies and lots of valuable minerals. Tyranny gives people cause to rebel. Poverty makes soldiering seem an attractive career option. Mineral wealth makes power lucrative to those who seize it.

Africa has all these problems in truckloads. Several wars that seem to have been extinguished are in fact only waiting to re-ignite, argue the pessimists. The skirmishing that continues in eastern Congo, for example, could easily re-escalate into all-out war. And since western powers are over-stretched in Iraq, Africans may find that they receive little help in putting out any new fires.

Optimists counter that Africans themselves have started to make more serious efforts to resolve their own conflicts. The two key peacemakers are the presidents of Africa’s richest and most populous nations respectively: Thabo Mbeki of South Africa and Olusegun Obasanjo of Nigeria. Mr Mbeki has worked hard to cajole warring factions into patching up their differences, with some success in Congo and Burundi. The affable Mr Obasanjo has acted as an honest broker between warring parties in Darfur, though without much yet to show for it.

The problem for Africa’s peacemakers is that no African army has the cash or planes to fly a large military force into hostile territory. They can deploy peacekeepers to neighbours that welcome them, or act as bodyguards for rebel leaders who lay down their arms and try to become politicians. But they cannot keep the peace where there is no peace to keep. For this, they would need substantial funding from abroad. At present they receive only dribs and drabs of cash, for example to help with the African Union’s mission to Darfur.

What to expect in 2005? The best guess is that Angola, Sierra Leone and Liberia will remain peaceful, and an uneasy stalemate will hold in Côte d’Ivoire. Despite forecasts to the contrary, Zimbabwe will not collapse into civil war, since only one side (the government) is armed. If Guinea’s ailing President Lansana Conté dies, there may be a coup there. Sudan will remain utterly wretched, as international efforts to halt the killing in Darfur will amount to a tiny fraction of what is needed. Congo will hang together, but only just.

Most African countries will remain stable, including the two most important: Nigeria and South Africa. Predictions that Nigeria’s ethnic violence could lead to civil war seem wildly implausible, and South Africa faces no visible threats. Africa will be less bloody than news footage suggests, but bloodier than Africans would wish.

Robert Guest: Africa editor, The Economist; author of “The Shackled Continent: Africa’s Past, Present and Future” (Macmillan)