Making news in Ethiopia

.

BBC News

The power of water to change lives - to destroy them as well as enhance them - is well chronicled. In regions like northern Africa, it is a commodity so precious that communities wither and die when they are denied it.

The Nile's source lies in Ethiopia,

which uses almost none of its water

|

Two angry eyes were squinting directly into mine through the glare of the midday sun.

Beneath them a jabbing forefinger stabbed the baking air, as its owner shouted and banged his foot on the ground. He was furious and it was all my fault.

I met, Mengistu, a 40-year-old Ethiopian farmer, while visiting the small village of Zaha in a remote part of northwest Ethiopia.

The rains have failed repeatedly over the last four years and virtually nothing grows anymore, leaving most local people dependent on food aid.

A big tributary of the river Nile flows right past these parched fields, yet there is no sign of any irrigation schemes. I asked Mengistu why.

"It's simple," he said, "my country is very poor, and has no money for such big schemes. That is why we stay hungry when the rain doesn't fall."

But did you know, I asked him, that your government says one reason why it cannot get help to pay for big irrigation schemes here is that Egypt has long been campaigning against them?

It totally relies on the Nile for virtually all its water and fears that such projects threaten its supply.

Anger

Mengistu, who looks remarkably like Ethiopia's answer to a middle-aged Ben Hur, had a question.

"What," he asked, "is Egypt?"

Ethiopia says it needs resources

to exploit the Nile's water

|

It is a large country to the north, way down the Nile from here, I replied.

Still quite calm, he placed a lined, weathered hand on my shoulder and asked another question.

"Will they give our water back?"

"Well, no," I told him, "but then they do not really see it as yours."

Then it happened. Swiftly, without any warning, this shy, polite, softly spoken farmer flew into a rage.

"Only a thief steals from you when you are not looking. That is what this Egypt has done," he bellowed.

"Why does our government and the world outside let them do this? If we had known, we would have dammed the river. That would have stopped them."

But I could not stop Mengistu.

His audience was growing bigger by the second and he was working himself into a frenzy.

"We will not let this go on. War is always a bad thing but the battle against hunger is even worse. We will fight if we have to!"

| |

So, here I was talking to a man who until this moment had developed a stoic acceptance of his fate.

Now, thanks to my arrival, he was mad as hell and threatening to whip up some form of watery Jihad.

'Urban oasis'

Was I covering the news or accidentally creating it?

It seemed a bit like the latter, but with the cat truly out of the bag, I decided to keep such thoughts to myself.

I was to do the same in down-stream Egypt just a few days later, when I came to witness something that should not have been happening, even though it evidently was.

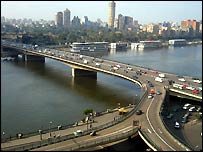

The Egyptians were keen to show me how their ingenious use of the Nile's waters is reclaiming vast areas of desert, and even enabling the creation of whole new towns on what had been nothing but parched wilderness.

Egypt's growing population is heavily

dependent on the Nile

|

Noubarya is one such place.

Egypt's Milton Keynes was established in 1987 and lies about three hours drive north of Cairo.

The town gets virtually no rain, yet canals linked to the river have made this spot an urban oasis.

I packed a large crate of bottled water and set off to see it.

About 20 miles from my target, the heavens opened. My taxi's windscreen wipers battled to cope with the onslaught from the sky.

As we drove into the town streams of water gushed down the street, turning potholes to puddles and then into lakes.

Completely ignoring the downpour, which seemed to be settling in for the day, a local spokesman enthused about this great desert miracle.

River Nile

How, without the Nile, his town would still be nothing but sand and dust, and, on he went, as the flood waters rose and passing pedestrians sprinted for cover.

Irrigation projects have enabled

Egypt to turn desert areas into productive land

|

But it is the only rainfall we have seen all year, he protested, as I brought his attention to the deluge outside.

"This is very, very rare!" he said.

All the more reason to report what I am seeing, I told him.

But then I started to think of the script line.

It might go something like this.

Here I am in a village where it never rains, except for today, when it is literally pouring.

But without downpours like this, this town could not survive if it was not for the Nile's waters, unless, of course, it keeps raining. Which I am told it will not.

Just would not work would it? Terribly confusing.

So in the end I have to confess that I left this dramatic rain storm out of my reports that followed. This omission is still on my conscience.

So too is Mengistu.

Happily, I have since heard that international bankers are now thinking of financing a large irrigation project near his village.

But I think I will leave it to someone else to tell him, just in case they go off the idea before I get there.